How the Other Half Plays

Reinventing Sara D. Roosevelt Park. Again.

By J.A. Lobbia*

The Village Voice

September 13th 1994 [apologies no archival link available that we could find but copy of article at the end]

When the city closes off the Houston Street end of Sara D. Roosevelt Park on Monday to begin a long –awaited renovation, there’ll be no throngs crowding the streets or hanging from the windows of surrounding tenements. No mayoral speech broadcast from Maine to Virginia, no cannon salute from Canal Street – all of which did accompany the park’s opening 60 years ago. But it will be a historic moment: The undertaking of a community project that faces virtually no opposition. In a neighborhood where everything from tree-plantings to bridge repairs must fend off a flurry of protest, where rare is the public plan that is not quickly followed by a lawsuit, there seems instead to be genuine consensus on the park rebuilding.

True, the consensus was reached only after about a decade of bickering, and partly because those who don’t like the final plans are either too tired or too disgusted to complain. But the fact is that for the last two years, the main emotion of those awaiting the city’s plans for the northern portion of the seven-block park is hopeful anticipation. Finally, there’s money, a contractor, and a suspiciously high level of optimism that the project will actually materialize.

But five blocks down and three weeks later, another project will begin here, one more typical of the neighborhood….

[more on this section of the park in a later post]

Between these two projects is a park thoroughly emblematic of New York City. Throughout its history, the 7.85 acres of SDR Park have been alternately the subject of grandiose, futuristic visions of urban planners, or the backdrop for the numbingly stark facts of city life, particularly life in a neighborhood packed with tenements and bordered by the Bowery.. The park itself is the spawn of a Tammany trick and a Moses mandate; home to picnics and murders, horseshoes and heroin. For generations, it has run through the city’s oldest slum, flanked first by Italians and Jews (the Italian March and the Jewish March were played at the inaugurals on September 14, 1934), now by Latinos and Asians.

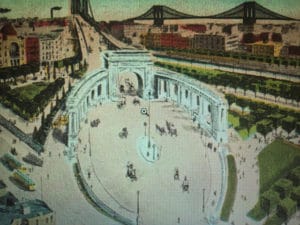

Sara D. Roosevelt Park cuts like a gutter through the Lower East Side, lined by Chrystie and Forsyth Streets. It is most lively at its south end, beginning at the Canal Street in the shadow of the grand ruin that is the approach to the Manhattan Bridge.

On summer mornings, Asians fill the space roughly from Hester to Grand Streets. The first to come are the old Chinese men who walk their hua mei birds in cages for several hours; by 9, the stroll is over. Other seniors being to take their places on benches and at chess tables sipping coffee or tea, or in the fairly new play areas, where they do tai chi in between swing sets and slides. Children follow, playing knock hockey, tabletop billiards, and board games supplied by the Police Athletic League. Further up, toward the Grand Street intersection, older kids fill the handball courts.

Across Grand, the park seems virtually deserted. The old sprinkler was here; now, it’s more a sunken latrine where men follow a certain etiquette, taking a stance at a favorite spot either to the left or fight along a low, redbrick wall.

At Broome Street sits a boarded-up park house, where a young man’s body was found several years ago; just beyond that, near Delancey, is a small community garden. The two tall corn plants seem out of place.

Crossing Delancey, a plague announces what might be the city’s most sadly named building: the Homeless Seniors Services center. In its fenced –in yard is a lush garden planted with help from the Parks Council and the Green Guerrillas [Sara RPCC]; a bocce court awaits construction.

To the east, near Chrystie, is the now infamous subway access door, subject of a recent report by Newsday’s Gale Collins lamenting the portal’s use as a refuge for thieves who count their booty there or store wheelchairs to be used as begging propos; the hatch covers a tunnel that leads all the way to the Broadway – Lafayette stop of the B, D, Q and F trains. The tunnels been a sore spot for years; Collin’s story has put everyone from the MTA to Manhattan Borough President Ruth Messinger into high gear, trying to balance anticrime measures against the fire department’s unmovable stance against locking the lid.

Further north, at Houston, the park is used in fits and starts by basketball-playing kids, [Ed. Note: mostly young Black women addicted to heroin and sold by their pimps for profit for use by mostly by white older men for sexual abuse] ‘sex workers’, and a few idlers. At the furthest reach stand four basketball hoops. On any Saturday afternoon from May to October for the last 18 years, a Mexican basketball league has taken over the court, along with as many as 200 picnickers. The parks department is looking for a replacement spot for the games during the renovation, which will extend from Houston to Delancey and last 14 months.

The park’s past is as varied as its present. Beneath Stanton and Rivington Streets lies the city’s second African Burial Ground, used from 1795 to 1853 – just after the one recently discovered at Duane and Broad way filled up. Not long after the last body was buried, developers came in and built row after row of tenement housing, packing in immigrants for maybe 50 years before Tammany Hall made its move.

In the late ‘20’s, Mayor Jimmy Walker was going to make grand improvements – widen Chrystie and Forsyth Streets, and erect ‘model’ housing for the poor (the Rockefellers were somehow involved) – but instead, the public was mugged. Walker’s plan was to demolish the slum and sell the land to developers cheap. But a Tammany judge – who disappeared and was never found- seems to have been in cahoots with the old tenement landlords. He awarded prices so high the city couldn’t afford to turn the now vacant land over to new developers at reasonable rates. The project sank, and the seven-block stretch sat empty until new Park Commissioner Robert Moses commandeered it in 1934. It became the city’s largest playground, and the biggest Lower East Side park to be developed since Tompkins Square had opened on Avenue A a hundred years before.

Moses, who compared SDR Park to Paris’s Rue de Rivoli, touted a refuge for the mothers and children of the neighboring slums. But the park eventually fell into the hands of people other than park planners, mothers, and children.

In 1959, a gang battle left a 15-year-old girl and a 14-year-old boy dead and two other boys wounded. Every few years, the body of a vagrant was found, sometimes slashed, sometimes near frozen. From the 1970’s to 1985, the city’s largest open-air heroin market ran in the park. “It was a tremendously colorful and exotic New York sight to see this group of people dealing with impunity, “ says Eric Roth, who runs the Bowery Residents Committee on Chrystie, which has been in the neighborhood 25 years. The trade dispersed east after mounted police busted the ring.

“Since then,” says Roth, “it’s become a much more typical, disgusting seedy NY Park.”

Though Moses intended to attract mothers and kids to Sara D. Roosevelt Park, his design makes it forbidding for many would-be users. All sidewalks are interior forcing pedestrians to walk either in the street or within the confines of the park, which is walled off by brick and wrought –iron fences and lined with trees. That gives a feeling of being enclosed, even trapped, in a sometimes uninviting place. Most playgrounds are below street level, making people feel hidden and vulnerable – or licensed to do something they shouldn’t. Even in the depth of the park’s best –planted garden or most populated playground, the feeling of being on a giant traffic-median is inescapable.

The renovation plans will change some of that. The sunken courts will be elevated to street grade, and ramps will be big enough to accommodate not only pedestrians but police cars. The four basketball standards will remain courts resurfaced with decorative parks department oak leaf [Ed. Note: It’s the London Plane leaf!] logos added. Ample lighting will line the area, and new slides, swings, and climbing toys will surround an abandoned park house. The old wrought –iron fence (pilfered I places by thieves from local antique shops [Ed Note:–and where did the rest go?] is to be renovated and replaced. And, perhaps in memory of Moses, the parks department will install benches from the 1964 World’s Fair.

It was around that time that Bob Humber moved to the neighborhood. Then in his early 20’s, he was an ardent basketball player. Now, he runs a 40-league team in the park for kids aged 6-18. He’s been a major advocate for park improvements, beginning by fighting plans about eight years ago to turn the whole park into a garden. Humber wanted to make sure kids could still play games there. “I was never much into gardening,” he admits,” he admits, though he did win a Parks Council grant to landscape the area behind the senior center. He did it with the help of some junkies who hung out in the park, most of them, he says, have since died.

Humber – who spends even his vacations in the park and who wears a shirt that announces “BOB” so you know just who you are talking to- has a complicated relationship with the junkies. He wants to keep the park for everyone including the Bowery overflow. He knows some of ht users from way back, when they were kids from his league.

“I caught a guy shooting up here once, and he said, ‘Oh Bob, I’m so sorry. I wish it was a police that caught me. I know you don’t like this.’” Just as junkies use the park as a sort of back-alley hideout, the city itself has treated it as a storage bin to serve other, more deserving oases. For instance, some original plans for Central Park were once found stored in an SDR park house, but city archives and even the parks department have little information on the downtown park itself.

That building there is a warehouse for city supplies, but we can’t even get a mop out of there if we want one,” Humber says. That should change with the renovation, when the warehouse becomes a rec center with Ping-Pong tables, a nursery, a theater, and a ‘safe haven’ program for neighborhood kids.

“We’ve been waiting for so long, now we just can’t wait till it will happen,” he says. “No one is fighting about this, and that’s because we’ve had the main event. But it’s all been worked out.”

[more on this part of the park in a later post concerning the area history around Grand Street.]

*A. Lobbia

NEW YORK (AP) — J. A. Lobbia, was an award-winning columnist and investigative reporter on housing and race relations.

Since 1990, Lobbia was an editor and reporter for the Village Voice in New York. She got her start writing about housing issues as an intern at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1983, and later was an investigative reporter and managing editor of the Riverfront Times in St. Louis. Lobbia’s articles in the Voice dealt with housing, community preservation, the elderly and immigrants. At the Riverfront Times, she wrote about black-on-black crime, black activism and racial imbalances in the judiciary. The Newswomen’s Club of New York recently gave Lobbia a Front Page Award for her reporting on housing. The Greater St. Louis Association of Black Journalists honored her four times for her work.